Yoga, a practice that has transcended its ancient origins in India, has become a worldwide phenomenon embraced by people from all walks of life. It is celebrated not only for its physical benefits, such as improved flexibility, strength, and posture but also for its mental and emotional benefits. It is a practice that promotes mindfulness, stress relief, and overall well-being.

However, over the years, a question has often emerged: “Is there a religion that doesn’t allow yoga?” This question is especially relevant given yoga’s deep ties to spiritual traditions, particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, and other Eastern philosophies. In this article, we will explore the relationship between yoga and religion, whether any religious doctrines expressly prohibit yoga, and the complex dynamics of yoga in different cultural and religious contexts.

The Origins of Yoga

Yoga has its roots in ancient Indian spiritual practices. The word “yoga” comes from the Sanskrit root “yuj,” meaning to unite or join, referring to the union of individual consciousness with the universal consciousness or divine. Historically, yoga was a deeply spiritual practice, intertwined with Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism, each using yoga as a means to attain spiritual enlightenment, self-realization, or liberation (moksha or nirvana).

The earliest reference to yoga is found in the “Rigveda,” a sacred text of Hinduism, where early forms of meditative practices and discipline were described. Over time, these practices evolved, and the “Yoga Sutras” of the sage Patanjali became a central text that outlined the philosophical foundations of yoga, focusing on ethics, meditation, and the goal of attaining a higher state of consciousness.

While yoga remains a prominent part of Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain traditions, in modern times, it has become increasingly secularized and adapted for purely physical or mental health purposes, devoid of its spiritual connotations for many practitioners worldwide.

Yoga and Religion: A Complex Relationship

Yoga’s relationship with religion is intricate. The practice, in its traditional forms, is closely tied to religious goals—particularly in Hinduism and Buddhism, where yoga is viewed as a means to achieve spiritual liberation. However, many people today practice yoga purely for physical or mental health benefits, disconnected from its spiritual or religious roots.

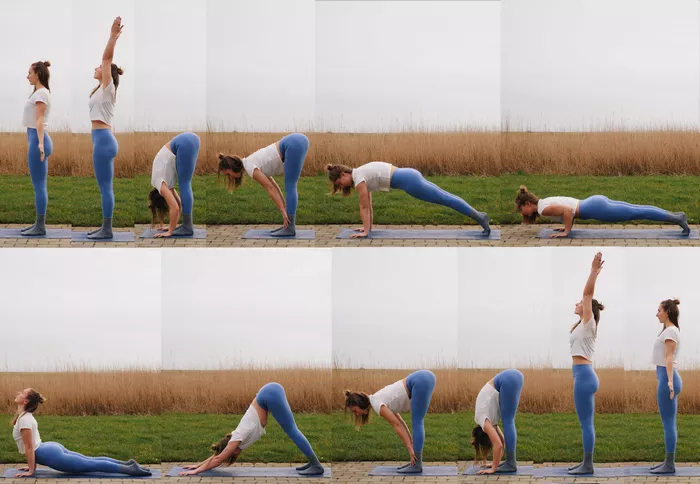

In fact, most contemporary yoga practices—especially those practiced in the West—focus primarily on physical postures (asanas) and breathing techniques (pranayama), while leaving aside the deeper spiritual aspects. This transformation has led to some practitioners regarding yoga as a secular or universal practice, accessible to people of all faiths or none at all.

However, despite its secular adaptations, yoga remains controversial in certain religious communities. While some religious traditions embrace yoga as a useful practice for enhancing physical and mental well-being, others view it with skepticism, particularly because of its deep connections to Eastern religions, or due to concerns over its potential to conflict with certain religious teachings.

Religions That May Have Reservations About Yoga

While yoga is generally seen as a neutral or even beneficial practice by most religions, certain religious groups and individuals have raised objections to yoga for various reasons. Let’s explore some of the main religious traditions that may express concern or opposition to yoga:

Christianity and Yoga

Christianity is one of the religions where yoga has met with resistance, particularly among certain evangelical and conservative groups. The primary concerns that some Christians have about yoga stem from its historical and philosophical ties to Hinduism, Buddhism, and other Eastern religious practices.

In particular, yoga’s emphasis on meditation and mindfulness has raised concerns about whether it involves the worship of false gods or idolatry. Some Christian critics view yoga as a form of spiritual discipline that could conflict with Christian teachings about the worship of God alone. The use of spiritual symbols, such as the Om symbol or the invocation of deities, in certain forms of yoga practice can also be seen as problematic from a Christian perspective.

That said, many Christian communities and individuals have adopted yoga as a physical practice, focusing on the physical benefits without engaging in its spiritual aspects. Christian yoga practitioners may refer to the practice as a form of exercise or relaxation rather than a religious or spiritual endeavor. In fact, there are even Christian yoga classes designed specifically to align with Christian beliefs, omitting any references to Eastern deities or spiritual practices.

Islam and Yoga

In Islam, there are also some concerns about yoga, primarily due to its origins in Hinduism and its connection to meditation practices. Islamic teachings emphasize the worship of Allah alone, and there is concern that meditation techniques used in some forms of yoga may lead practitioners toward spiritual paths that conflict with Islamic doctrine.

However, like Christianity, Islam is not monolithic, and views on yoga can vary widely among different communities and schools of thought. Some Islamic scholars and practitioners have no objection to yoga as a physical practice that does not interfere with the core tenets of Islam. Others may argue that yoga’s spiritual aspects, particularly meditation and breathwork, could interfere with a Muslim’s devotion to Allah.

In regions like Indonesia and the Middle East, where Islam is the dominant religion, yoga may be seen with more skepticism. But in other parts of the Muslim world, such as parts of South Asia, yoga is widely practiced, especially for health and fitness purposes, without any religious concerns.

Judaism and Yoga

Judaism’s perspective on yoga is more nuanced. Traditional Judaism does not have specific prohibitions against yoga; however, like Christianity and Islam, there are concerns about the practice’s connection to Eastern spirituality. Some Jewish communities may view yoga’s origins in Hinduism and Buddhism as incompatible with Jewish beliefs about God and spirituality.

Despite these concerns, many Jewish individuals and communities practice yoga, focusing on its physical benefits and personal well-being rather than its spiritual or religious connotations. In some cases, Jewish practitioners of yoga may modify the practice to align more closely with their faith, using prayer or Jewish meditations instead of traditional mantras or meditation techniques.

Other Religions: Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism

Yoga remains an integral part of Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism. In these religions, yoga is seen as a spiritual discipline that helps individuals attain self-realization, enlightenment, and liberation. For followers of these faiths, yoga is not merely a form of physical exercise, but a sacred practice that deepens one’s connection to the divine.

In Hinduism, yoga is viewed as one of the paths to moksha (liberation), and there are various forms of yoga, including Bhakti Yoga (the path of devotion), Karma Yoga (the path of selfless action), and Jnana Yoga (the path of knowledge). Similarly, in Buddhism, yoga (often in the form of meditation) is central to the practices of mindfulness, concentration, and insight, helping practitioners achieve enlightenment.

For adherents of these religions, yoga is not seen as contradictory to their faith but is rather an essential part of spiritual practice. However, this does not necessarily mean that all forms of yoga are universally accepted in all sects or traditions within these religions.

Can Yoga Be Practiced by People of All Religions?

In modern times, yoga has been widely adopted by people from various religious backgrounds, often as a physical practice that helps improve flexibility, strength, and overall fitness. Many people who practice yoga do so without any religious affiliation, focusing solely on the physical postures (asanas), breathwork (pranayama), and relaxation techniques.

In this secularized form, yoga is often seen as a universal practice that can be beneficial to anyone, regardless of their religious beliefs. In fact, many Western yoga instructors emphasize yoga’s non-religious aspects, encouraging students to focus on the physical and mental health benefits without delving into its spiritual origins.

For individuals of faith, yoga can be adapted to suit personal beliefs. For example, Christian yoga practitioners may focus on prayer and meditation aligned with Christian teachings, while Muslims may practice yoga with an emphasis on mindfulness and physical postures that align with Islamic principles. Many yoga instructors today offer classes that are inclusive and adaptable to people of various religious backgrounds, ensuring that the practice can be enjoyed by everyone in a way that is meaningful to them.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is no one-size-fits-all answer to the question of whether yoga is allowed or forbidden by different religions. While certain religious groups, particularly conservative Christian and Islamic communities, may have reservations about yoga due to its spiritual origins in Hinduism and Buddhism, yoga, in its modern form, has become a secular practice that focuses on physical health, relaxation, and stress relief.

For many people around the world, yoga has become a universal practice that transcends religious boundaries. It is important to note that yoga is highly adaptable and can be practiced in a way that aligns with one’s personal beliefs, whether those beliefs are religious or secular.

In the end, the decision to practice yoga is a personal one, and it is up to each individual to determine whether the practice resonates with them, based on their spiritual, cultural, or personal values. For those who feel uneasy about yoga due to religious reasons, it is always possible to modify the practice or seek alternative forms of exercise that are more in line with their beliefs.

Yoga, at its core, is about unity—whether that’s the union of body and mind, self and others, or individual consciousness with the universe. It is a practice that can be adapted to fit the needs and values of individuals from diverse religious and cultural backgrounds.

Related Topics: